Do machines have the ability to think?

In the first half of the 20th century, science fiction introduced the world to the concept of robots with artificial intelligence. I remember being engrossed in science fiction books, starting with the ‘heartless’ Tin Man from ‘The Wizard of Oz’ and continuing with a humanoid robot posing as Maria in ‘Metropolis,’ all borrowed from the library.

By the 1950s, we had a generation of scientists, mathematicians, and philosophers for whom the concept of artificial intelligence (AI) had been culturally assimilated.

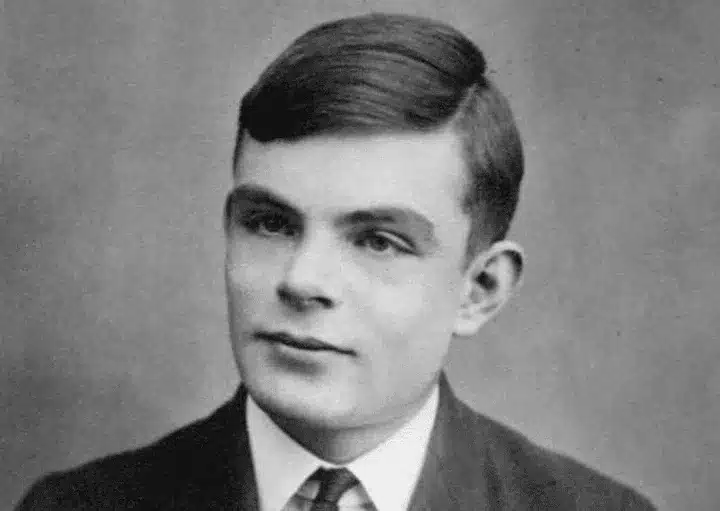

One such individual was Alan Turing, a young British polymath who explored the mathematical possibilities of artificial intelligence. Turing speculated that humans use available information and reason to solve problems and make decisions, so why couldn’t machines do the same?

This formed the logical basis of his 1950 article, ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence,’ in which he discussed how to create intelligent machines and how to test their intelligence.

Everything is possible; the boundaries are in our minds.

Turing’s work and all of his advancements existed primarily as discussions and theories. This was due to several factors. First and foremost, significant changes in computer technology were necessary to materialize these ideas.

Up until 1949, a critical requirement for intelligence was lacking in computers — they were unable to store commands and were designed solely for execution.

In simpler terms, you could instruct computers on what to do, but they couldn’t retain a memory of their actions. Additionally, computing technology was an exceedingly expensive luxury during the early 1950s.

Renting a computer could cost as much as $200,000 per month, making it accessible only to prestigious universities and large technology companies.

Developing artificial intelligence required not only confirmation of the concept but also support from investors to convince funding sources of its worthiness.

The Conference that Started it All

The proof of concept was initiated in The Logic Theorist, a program designed to simulate human problem-solving skills and funded by the Research and Development Corporation (RAND).

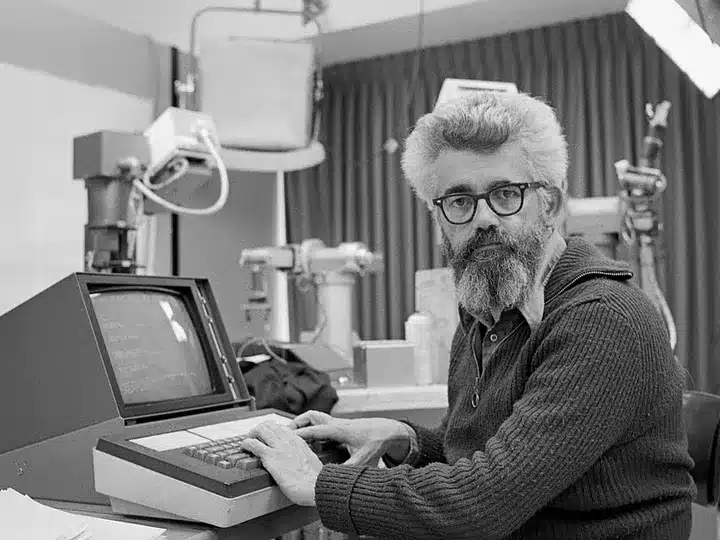

It can be considered the first artificial intelligence program and was presented at the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence (DSRPAI) organized by John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky in 1956.

John McCarthy. Source: The Independent

At the historic McCarthy conference, envisioned as a collaborative effort, McCarthy, along with leading researchers from various fields, presented for open discussion the concept of artificial intelligence — a term he coined at the event.

Unfortunately, the conference did not meet McCarthy’s expectations; people came and went as they pleased, and there was no consensus on standard methodologies in this field.

Despite this, everyone sincerely agreed that AI was achievable. The significance of this event cannot be underestimated, as it catalyzed the next twenty years of AI research.

Roller Coaster of Success and Failure in AI

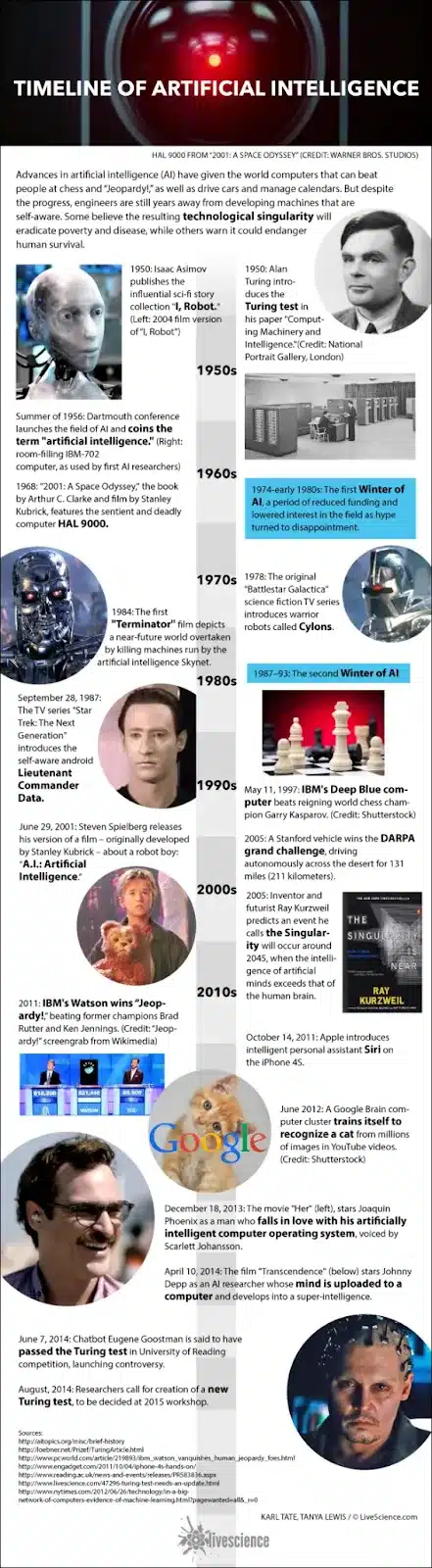

From 1957 to 1974, AI thrived. Computers could store more information and became faster, cheaper, and more accessible. Machine learning algorithms also improved, and people gained a better understanding of which algorithm to apply to their problems.

Early demonstrations, such as Newell and Simon’s “General Problem Solver” and Joseph Weizenbaum’s ELIZA, showed promising results in problem-solving and speech interpretation, respectively.

These successes, coupled with the support of leading researchers (particularly participants in DSRPAI), convinced government institutions like the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to fund AI research in various institutions.

The government was particularly interested in a machine that could decipher and translate spoken language, as well as perform high-performance data processing. Optimism was high, and expectations were even higher.

In 1970, Marvin Minsky told Life Magazine, “In from three to eight years, we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being.” However, despite the existence of foundational evidence, there was still a long way to go before achieving the ultimate goals of natural language processing, abstract thinking, and self-awareness.

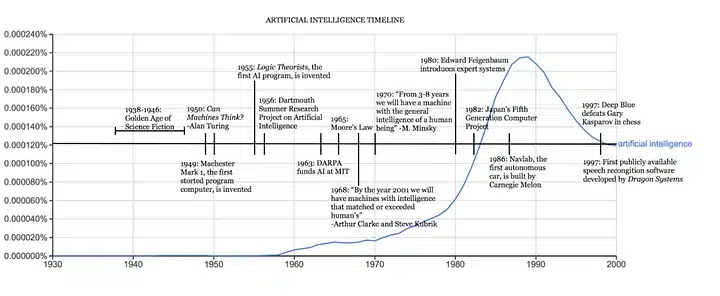

AI Timeline. Source: sitn.hms.harvard.edu

Breaking through the initial fog of AI, we discovered a mountain of obstacles. The most significant one was a lack of computational power to accomplish anything substantial: computers simply couldn’t store enough information or process it quickly enough.

For instance, to communicate, one needs to know the meanings of many words and understand them in various combinations. Hans Moravec, then a McCarthy Fellow, stated that “computers were still millions of times too weak to exhibit intelligence.” As patience waned, so did funding, and progress in research slowly inched forward over a decade.

In the 1980s, the development of artificial intelligence resumed thanks to two sources: the expansion of algorithmic tools and increased funding. John Hopfield and David Rumelhart popularized “deep learning” methods that allowed computers to learn from experience.

On the other hand, Edward Feigenbaum introduced expert systems, simulating the decision-making process of a human expert. The program would ask an expert in a specific field how to react in different situations, and once practically learned for each situation, non-experts could seek advice from the program.

Expert systems gained widespread use in the industry. The Japanese government actively funded expert systems and other initiatives related to artificial intelligence under its “Fifth Generation Computer Project” (FGCP).

Edward Feigenbaum Source: britannica

Between 1982 and 1990, they invested $400 million in revolutionary computer processing goals, the adoption of logic programming, and the improvement of artificial intelligence. Unfortunately, most ambitious goals were not achieved.

However, it can be argued that the indirect consequences of FGCP inspired a talented young generation of engineers and scientists. Nevertheless, FGCP funding ceased, and AI fell out of the limelight.

Ironically, in the absence of government funding and public buzz, AI thrived.

In the 1990s and 2000s, many landmark goals of artificial intelligence were achieved. In 1997, world chess champion and grandmaster Garry Kasparov was defeated by IBM Deep Blue, a computer program for playing chess.

This widely publicized match marked the first defeat of a reigning world chess champion by a computer and served as a significant step toward decision-making programs with artificial intelligence.

In the same year, speech recognition software was implemented on Windows, developed by Dragon Systems. This was another significant step forward in the direction of oral translation.

It seemed there were no problems machines couldn’t handle, even human emotions, as evidenced by Kismet, a robot developed by Cynthia Breazeal that could recognize and display emotions.

Time heals all wounds

Have we become smarter in how we encode artificial intelligence, and what has changed?

It turns out that the fundamental limit of computer memory, which held us back 30 years ago, is no longer a problem. Moore’s Law, stating that the memory and speed of computers double every year, has finally caught up with and in many cases exceeded our needs.

This is how Deep Blue managed to defeat Garry Kasparov in 1997, and Google AlphaGo defeated Chinese Go champion Ke Jie just a few months ago.

This provides some explanation for the roller coaster in AI research; we saturate AI capabilities to the level of our current computational power (computer memory and processing speed), and then wait for Moore’s Law to catch up with us again.

Artificial intelligence is everywhere

Now we live in the era of ‘big data,’ a time in which we can collect vast amounts of information, too cumbersome for human processing. The application of artificial intelligence in this regard has already proven to be very fruitful in several industries, such as technology, banking, marketing, and entertainment.

We have seen that even if algorithms do not significantly improve, big data and massive computations simply allow artificial intelligence to learn through brute force.

There may be evidence that Moore’s Law is slowing down the pace, but the growth of data volume has certainly not lost momentum. Breakthroughs in computer science, mathematics, or neurobiology — all these are potential avenues beyond the limits of Moore’s Law.

AI Around the World: Countries embracing Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Singapore

Singapore ranks second in the number of people interested in creating images using AI (281). Due to the popularity of AI in Singapore, the country plans to triple the number of experts in artificial intelligence, including scientists and engineers in machine learning, to 15,000 as part of its national artificial intelligence strategy, said Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong.

The Southeast Asian country with a population of 5.45 million people, home to the Asian headquarters of global tech giants such as Alphabet (GOOGL.O) and Microsoft (MSFT.O), owned by Google, stated that it will also work on enhancing its available high-performance computing resources by providing access through partnerships with chip manufacturers and cloud service providers.

Latin America

Latin American countries lead in the field of AI-generated audio. The most popular AI-generated audio tool in the world is FakeYou: it is searched for 172,000 times monthly.

These tools can reproduce the voices of well-known musicians and other celebrities with astonishing accuracy, sparking copyright disputes involving Drake and The Weeknd after someone created a new song using their voices, reports The New York Times.

Ukraine

Ukrainian AI-powered UAVs have not only opened up numerous prospects for the military but also revolutionized the “drone war” worldwide.

The Ministry of Defense of Ukraine reported issuing permission to supply Saker Scout unmanned aerial systems to the Armed Forces of Ukraine. The drone’s software is built on artificial intelligence algorithms.

Ukraine has become an innovator among UAV developers and attracted investments from notable entrepreneurs, including donations from the CEO of one of the largest European crypto exchanges — WhiteBIT, Volodymyr Nosov, and former Google CEO Eric Schmidt.

Conclusion

The contemporary era, marked by the prevalence of ‘big data,’ has propelled AI into various industries like technology, banking, marketing, and entertainment.

As we navigate the AI revolution, it’s evident that AI is a global phenomenon with diverse applications. Countries such as Singapore, Latin American nations, and Ukraine showcase unique ways of embracing AI, impacting image creation, audio generation, and military capabilities.

The AI journey is a testament to human ingenuity and the pursuit of knowledge. Past challenges have paved the way for the current era of AI ubiquity, and the future promises exciting developments as we push the boundaries of machine capabilities.

While the question of machines truly thinking remains philosophical, the practical applications of AI in daily life are undeniable, shaping the course of technological evolution.